While Washington managed to avoid the fiscal cliff last month, Alaska appears to be edging closer to its own precipice in the not-too-distant future.

The non-partisan Legislative Finance Division has warned lawmakers that continuing State spending at the historic rate of growth, or maintaining spending at current levels in an era of steadily declining oil production, could put Alaska’s economy at risk. (See side-bar on page 5).

Prominent Alaskan economist Scott Goldsmith also set off alarm bells when he warned Alaska faces a mounting fiscal gap, which could result in an economic crash.

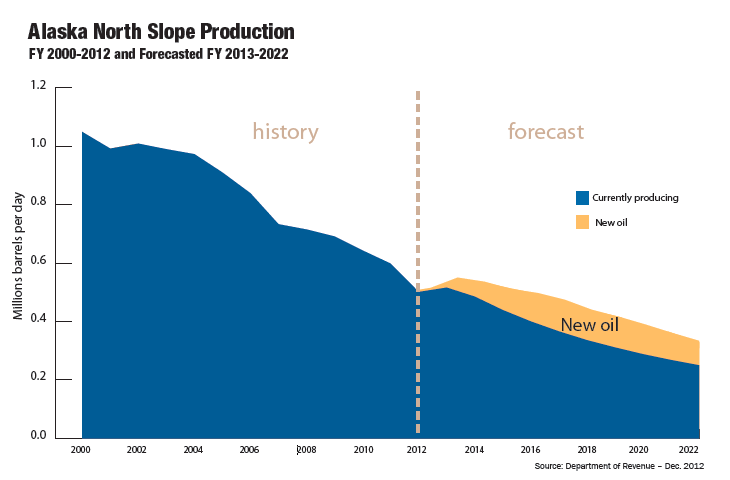

With current tax rates on North Slope oil producers capturing most of the profits otherwise earned by oil companies in a high price environment, there has been a massive re-allocation of investment dollars from Alaska to other more inviting oil and gas jurisdictions. The flight of capital has resulted, in part, in a decline in North Slope oil production of 6-8 percent annually.

This is bad news since oil production accounts for more than 90 percent of Alaska’s unrestricted General Fund revenues.

With oil production in steep decline, throughput in the Trans-Alaska Pipeline System (TAPS) has fallen sharply. The pipeline is now operating at one-quarter the volume it once carried.

However, the State has continued to run budget surpluses as high oil prices have masked the decline. But the trend of increased spending with decreasing production is not sustainable, economists warn.

The Alaska Department of Revenue is forecasting oil production to fall by an average of 5.5 percent annually. Higher forecasted oil prices are expected to offset a large portion of the lost revenues associated with the production decline, but state spending on agency operations have been increasing an average of 6.5 percent a year.

Governor Sean Parnell recently released his budget for the next fiscal year, and it is nearly $1.1 billion less than the current year’s General Fund spending. In its proposal, the administration holds the State’s share of the operating budget to less than one percent growth at $6.49 billion. The new budget leaves approximately $500 million in surplus revenue for FY14.

While the governor’s proposed general fund spending is less than the current year’s budget, it is still not sustainable, according to Goldsmith, an economist with the non-partisan Institute of Social and Economic Research (ISER) at the University of Alaska Anchorage.

In FY 14, Alaska’s state government can afford to spend about $5.5 billion, said Goldsmith. That’s an estimate of the level of unrestricted General Fund spending the state can sustain over the long run, based on the current petroleum nest egg of about $149 billion — a combination of state financial assets, including the Permanent Fund and cash reserves, and the value of petroleum still in the ground.

The size of that nest egg fluctuates, depending on the state’s forecast of petroleum revenues, earnings on investments, and other factors, Goldsmith said. In an updated fiscal report, Goldsmith presented the latest in a series of estimates of the maximum amount the state can spend and still stay on a sustainable budget path.

“Right now, the state is on a path it can’t sustain,” Goldsmith said. “Growing spending and falling revenues are creating a widening fiscal gap.” (See chart at right).

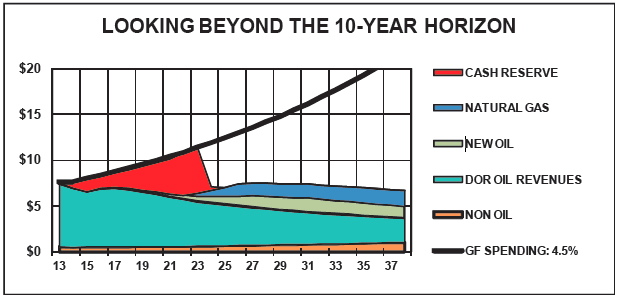

In a 10-year fiscal plan, the State Office of Management and Budget (OMB) projects that spending cash reserves might fill this gap until 2023. But what happens after 2023?

“Reasonable assumptions about potential new revenue sources suggest we do not have enough cash in reserves to avoid a severe fiscal crunch soon after 2023, and with that fiscal crisis will come an economic crash,” Goldsmith warned.

If spending increases at a rate of 4.5 percent annually, there will be a growing fiscal gap, even assuming new revenues from natural gas production and some additional oil production, Goldsmith noted. To avoid a major fiscal and economic crisis, the State must save more and restrict the rate of spending growth, Goldsmith said. To avert a crisis, all revenues above the sustainable spending level of $5.5 billion — including Permanent Fund income, except the share that funds the dividend — should be channeled into savings, Goldsmith said. He emphasized that new oil production alone will not solve the fiscal gap.

If Alaska had $38 billion in cash reserves and $79 billion in the Permanent Fund by 2023, the State would be on the path to sustainable spending far into the future, Goldsmith said. But that’s twice what the State has in financial assets today – $17 billion in cash and $43 billion in the Permanent Fund. So the State needs to sharply step up its savings rate, the ISER report noted.

New broad-based income and sales taxes would postpone but not eliminate the fiscal crunch. Even using the entire Permanent Fund would not avoid a crisis as the fund would run out soon after 2038. Alternatively, holding growth of the budget to the rate of inflation would reduce the size of the fiscal gap, but postpone it only five years.

Maximum sustainable yield

In his report, Goldsmith introduced what he called a maximum sustained yield strategy. He defined it as the amount the State can spend each year from its petroleum endowment, or nest egg, and still sustain the value of that nest egg for future generations. The amount the State can spend each year depends on the size of the nest egg, the return it can achieve through prudent management of the nest egg, and the time it will need the nest egg to sustain public spending.

“If the petroleum nest egg has a value of $149 billion, if it can be managed to generate a five percent return, and if it is to increase over time to account for population growth, the maximum sustainable yield would be $5.95 billion,” Goldsmith said.

“In contrast to business-as-usual, there is no fiscal cliff associated with the maximum sustainable yield strategy,” Goldsmith said. “Enhanced financial resources, combined with new revenues from long-term petroleum developments, would be sufficient to cover General Fund spending growing with population. Over time, the declining value of oil and gas in the ground would be replaced by the growing value of financial assets. These financial assets would gradually become the most important source of revenues for the General Fund.”

A Ten-year plan

Plotting a course for the next ten years, the State’s OMB has updated its ten-year revenue plan. In the plan, OMB said Alaska must continue to make strides to maximize production from existing oil fields and develop other economic opportunities, particularly from its abundant natural resource base.

The ten-year plan examines a range of possible spending and revenue scenarios, taking into account population growth, inflation, and obligations.

“The upward pressure on spending is significant,” OMB stated in a summary of the plan. Challenges that must be considered, while providing a reasonable level of State services, include tax credits for oil and gas development, the unfunded public employee and teacher retirement systems, Medicaid spending, addressing the high cost of energy for Alaskans, and maintaining aging State-owned infrastructure.

OMB stressed, “Alaska’s future prosperity hinges on the development of its natural resources.” It noted that the Alaska Statehood Act was in part based on the development of natural resources to provide for a stable economic base, which would reduce the likelihood that Alaska would be a drain on the federal treasury. To date, the strategy of building Alaska’s economy on natural resources has been successful.

But the declining flow of oil poses a direct threat to the economy, OMB warned. “The best way to grow Alaska’s economy for all and avoid a premature shutdown of the pipeline is to boost the flow oil into TAPS.”

The administration is implementing a four-part strategy to address the decline, including increasing production by making Alaska more competitive for investment, ensure the permitting process is structured and efficient, facilitate the next phase of North Slope development, and promote Alaska’s resources to world markets.

Spending scenarios

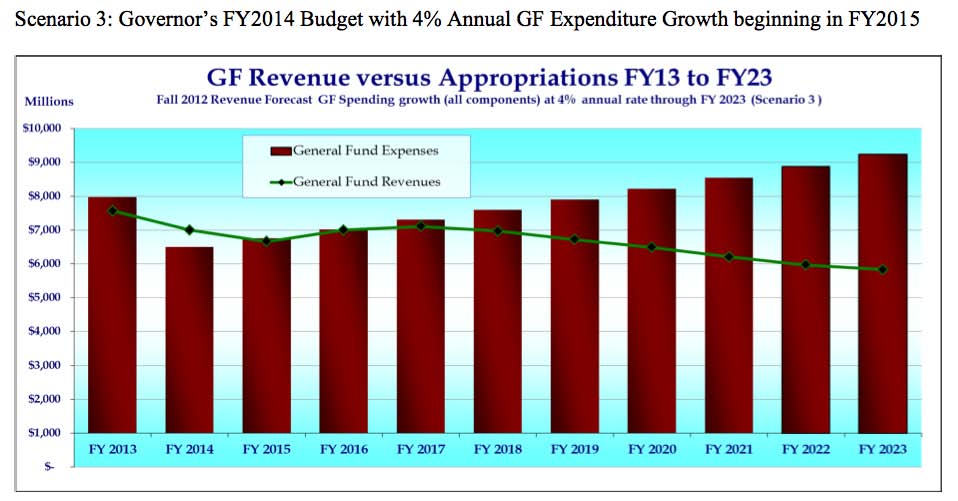

To illustrate what may lie ahead, the 10-year plan models three spending scenarios and one alternate oil price scenario.

Its first scenario is based on the Fall 2012 oil price and production forecast and assumes flat General Fund spending of $6.5 billion. Budget deficits develop in 2019 and build steadily from there.

In scenario two, oil prices fall to $90 a barrel, annual spending is held to $6.5 billion, the capital budget is set at $200 million, and the status quo prevails for state obligations. Budget shortfalls would begin in FY 13 with multi-billion dollar deficits beginning in FY 14. Reserve accounts run out by 2020.

Scenario three assumes an FY 14 budget of $6.5 billion with four percent annual spending growth of the General Fund beginning in FY 15, while assuming the Fall 2012 price and production forecast. A budget surplus in FY 14 turns to a continuous draw on reserves beginning in FY 15. Reserves peak in FY 18 and experience a steady draw.

Scenario four is based on the Fall 2012 oil price and production forecast with four percent agency spending growth, a Capital Budget at $1 billion, and State assistance payment growth. Under this scenario, a budget surplus in FY 14 turns to continuous draws on reserves in FY 15 and deficits steadily grow.

Return to newsletter headlines