In his State of the State address in January, Governor Sean Parnell repeatedly called for “meaningful tax reform” to Alaska’s oil production tax structure, a top priority of Alaska’s major business associations whose member companies combined employ tens of thousands of Alaskans across all economic sectors of the state.

Parnell said meaningful tax reform would move the needle on attracting the industry investment that is required to stem the accelerating decline in North Slope production and increase production over the long term, leading to higher state revenues and a stronger private sector economy.

The governor insists House Bill 110, which passed the House last year but is unlikely to move in the Senate, would result in significant reform of the tax structure and attract new investment in projects that would put new oil into Alaska’s economic lifeline, the Trans-Alaska Pipeline System (TAPS).

“I’m not looking to increase production by just a couple of thousand barrels or 10,000 or 20,000 barrels,” Parnell said. His goal is to reverse the accelerating production decline and increase TAPS throughput from the current 600,000 barrels per day to one million barrels per day within ten years.

The governor noted that oil companies have already committed billions of dollars in new investments – if the legislature passes meaningful tax reform. He said “significant new investment in oil production would be a game changer for our state – a down payment on Alaska’s future we cannot afford to turn down.”

Reforming oil production taxes has widespread support among Alaska business leaders. At the Anchorage Economic Development Corporation’s (AEDC) annual luncheon last month, attended by over 1,500 Alaskans, it was announced that 72 percent of business executives in the Anchorage area now believe the state’s oil and gas tax structure is negatively impacting North Slope oil production. The poll was included in AEDC’s fourth annual Business Confidence Index Survey of Anchorage businesses and organizations.

“The question before us now is not whether we have enough oil reserves to meet our goals,” Parnell said. “The question is this: Do we have enough will to give up short-term gains for long-term growth?”

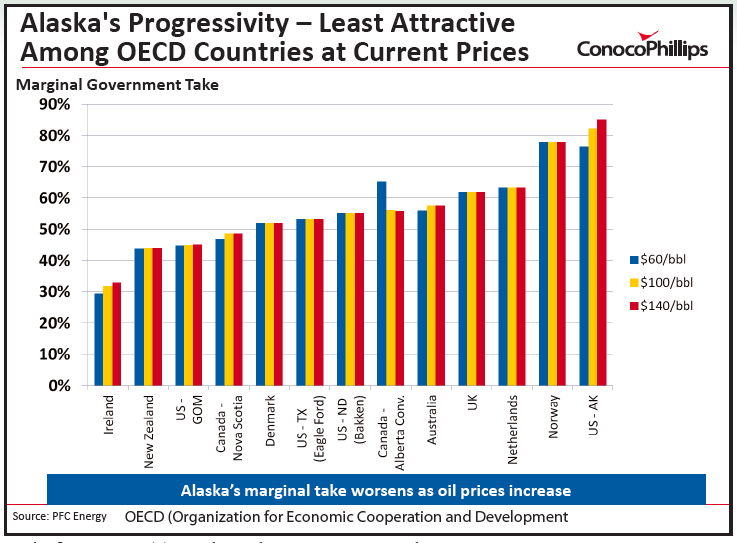

Alaska’s production tax is structured to increase as crude oil prices rise. At high oil prices, Alaska’s tax is among the highest in the world, and that is on top of large Arctic development and operating costs.

Proponents of the oil tax reform want to reduce the tax by changing the “progressivity” formula in the fiscal regime that causes the tax rate to escalate at high prices. As presently structured, there is little upside potential at high oil prices for producers investing in new production. The return to them is about the same at lower oil prices as it is at high prices, an unattractive way for an oil company to invest.

This in large part is why Alaska is not competitive in attracting the investment it should at high prices. With lower costs and taxes, the Lower 48 states are seeing a surge of new investment and Alaska is not.

What form oil tax reform takes may now largely be up to the Senate, where key policy makers were expected to introduce a reform bill in the Resources Committee when this publication went to press in early February. The panel will send the bill to the Finance Committee, the Senate floor, and the House. Among other things, it is expected to address progressivity, but differently than the governor’s bill, HB 110.

“My desire is that anything this Legislature passes significantly increases production investment in the state,” Parnell said, adding he would judge legislation on whether it moves “the meter on production significantly like HB 110 does.”

In response to recent arguments cited by opponents of HB 110 that TAPS may be able to operate at low flow levels, Representative Eric Feige acknowledged it may be theoretically possible to operate the pipeline down to 100,000 barrels a day with the resulting small profit, but he warned funding state government becomes extremely challenging at that level. He also warned that the pipeline at low flow levels would be less resilient when a shut down occurs.

In a recent Petroleum News interview, he suggested the legislature look at what point in the production curve does the state income tax have to be reinstated to pay for government, rather than debate how low TAPS throughput can go.

Feige noted the current year’s budget balances at $94 a barrel. Assuming a six percent decline in production and a seven percent increase in the budget, in four years the state will need an oil price of $142 per barrel to break even, Feige said. That’s a budget shortfall of 30% at today’s prices.

The state’s 2011 fall revenue forecast predicts that if the current decline trends continue, Alaska will be in deficit territory by 2015.

Speaking at the Alliance’s Meet Alaska Conference last month in Anchorage, John Minge, President of BP Exploration (Alaska), Inc., said his company welcomes Parnell’s goal of increasing TAPS throughput to one million barrels per day.

“We believe the goal is achievable,” Minge said. However, he said for such a goal to be achieved, the state will need to attract billions of dollars in increased investment, which in turn will be contingent on a tax regime that encourages such investment.

Minge said BP’s capital investment in Alaska is declining, while ConocoPhillips’ investment remains flat.

He explained that in the summer of 2007, prior to the passage of the current production tax, BP had planned a capital budget for Alaska of $1.2 billion for 2012; the actual budget is about $650 million. He warned that at the current investment rate, “we guarantee a six to eight percent decline” per year in production.

At the ongoing rate of decline in North Slope production, throughput in TAPS will fall to 300,000 barrels per day in 2020, Minge estimated. And at the current rate of increase in the state budget, it would take $220 per barrel oil to balance the budget in eight years, he said.

TAPS throughput is already lower than what the 2007 state revenue forecast projected for 2020. Meanwhile, the state warned in its most recent forecast that half of its revenue stream in 2020 will depend on industry investments that have yet to be made.

Minge said only 35 percent of BP’s capital budget in Alaska is aimed at sustaining oil production. Forty percent is going into infrastructure maintenance and renewal and 25 percent into technologies for heavy and viscous oil and gas. He said only one out of six of BP’s North Slope employees is working in jobs involving new production with the rest “focused on operating, maintaining, and repairing facilities that are already there.”

ConocoPhillips has said that most of its capital budget is allocated to maintenance.

Minge outlined several projects as part of the $5 billion in investment opportunities that BP sees on the North Slope, but only with meaningful tax reform. “When the investment climate improves and our projects are commercially viable, we’ll be able to move,” he said. “If HB 110 were to pass, there are many projects we would start working immediately."

Minge emphasized that the state is in the oil business – it makes money and its economy prospers when industry invests.

“Under the current tax structure, the state is actually squeezing the life out of the industry by making investments in new oil unattractive; by taking the returns now, rather than over many years; by removing revenues at a rate which simply is not sustainable for our long-term future.”

ConocoPhillips chief economist, Marianne Kah, noted there are many places for the oil industry to invest and Alaska does need to compete for capital.

Kah said Alaska’s progressivity tax structure is severely limiting investment and production here. She said Alaska’s marginal tax rate is a major factor in determining the state’s competitiveness with other oil and gas provinces. She pointed out that the total local, state and federal government take can rise as high as 90 percent at the high end of the price spectrum.

In a sobering comment, Kara Moriarty, Executive Director of the Alaska Oil and Gas Association, predicted that “until we see a change in the (tax) culture here, we’re not going to see the type of development that can stem the decline.”

Opponents of oil production tax reform are not convinced that industry will respond with increased investment in Alaska if the governor’s bill reforming oil taxes passes this session. They note that even though taxes were low between 1996 and 2006, oil production continued to decline.

However, between 1996 and 2003, the price of oil averaged less than $20 per barrel, having a serious impact on industry investments in high-cost jurisdictions, like Alaska. Prices fell as low as $10 a barrel during this period, forcing wide spread lay-offs and a wave of company mergers. Over the entire 10-year period, prices averaged under $32 per barrel, suppressing investments and production.

Return to newsletter headlines